When my daughter was about a year old, she started having these… episodes. They were eerily similar to a night terror, except she didn’t seem conscious. Her eyes were opened, yet unfocused. She couldn’t stand or hold her arm up. She didn’t respond to light or sound. She was, essentially, catatonic. There’s really nothing to compare it to; our bright, vivacious, full-of-smiles little girl was just a shell. We were left to wonder since these “episodes” were predominantly presented at night. And worry.

When my daughter was about a year old, she started having these… episodes. They were eerily similar to a night terror, except she didn’t seem conscious. Her eyes were opened, yet unfocused. She couldn’t stand or hold her arm up. She didn’t respond to light or sound. She was, essentially, catatonic. There’s really nothing to compare it to; our bright, vivacious, full-of-smiles little girl was just a shell. We were left to wonder since these “episodes” were predominantly presented at night. And worry.

We had some inkling of what these episodes were. My daughter has a rare genetic condition, which is often associated with a higher rate of epilepsy. I wrote about it when I shared her diagnosis, Sotos Syndrome, She’s Rare. There is a hard line to walk when you’re dealing with a complicated medical diagnosis; my number one rule is, ‘don’t borrow trouble.’ Educate yourself just enough to not ultimately drive yourself crazy with the potential “what-ifs.”

The trickiest part of an epilepsy diagnosis is that unless you happen to have a camera and an EEG connected at that perfect moment, there’s only so much a physician can do. So we recorded everything, we took videos, we kept a journal, and we timed how long each episode lasted. We went to ERs, visited specialists, and waited. The problem with waiting is that no seizure is a good seizure. Rule #1 in Epilepsy is the goal is never to have a seizure. While we waited, we were having seizures. All of our “evidence” goes into a list, but that list hasn’t really brought us to an official diagnosis.

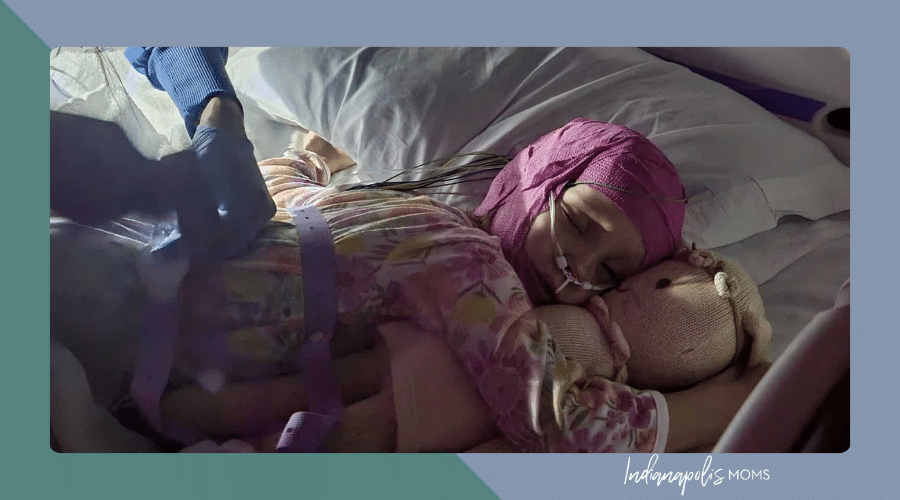

Then, one day, my oldest son announced to the car from the backseat that his sister was blue and shaking, and it all just changed. A Grand Mal, or Tonic Clonic, seizure typically begins with a loss of consciousness, sometimes meaning the patient isn’t breathing, then violent jerking or shaking movements. This part can last for up to five minutes- and it did for us that day. The period after a seizure is called your Postictal Phase and can last from minutes to days. This is often just a scary as the actual seizure, for us, it’s catatonic almost. It’s like everything that makes her “her” has been wiped away, and she is just a shell of herself. Sometimes, it’s minutes, and other times, it’s hours. Then, suddenly, she just “wakes up” and looks around, wondering why we’re all staring at her or how she got in a hospital room or ambulance.

There is no “cure” for epilepsy. There is a hope that the correct medication regime can be found (there’s a lot more tricky waiting and trial and error here) and epilepsy can be managed. For us, that means seeing a neurologist every three months so she can be weighed and measured and her correct dosage can be calculated down to its most minute calculations. She receives that medication orally every twelve hours, like clockwork; She has to have this med in her system every minute of the 24-hour period. A missed med, even a late one, can mean a seizure. The goal is always no seizure but there are also Emergency Rescue Medications that can be administered, in our case, if a seizure lasts longer than three minutes we would administer a medication rectally to stop a seizure. This means that we carry it EVERYWHERE. Even a quick walk around the neighborhood. She has a dose in the school nurses office, if she goes on a playdate it’s in her backpack. And it can’t get too hot or too cold, so think about that everywhere you go. If you spend enough time with our family, we will walk you through the dos and don’ts and encourage you to familiarize yourself with seizure first aid.

While I do think that people go on to live perfectly normal lives, it is important to know that epilepsy is serious. If you have a friend named Anxiety and epilepsy joins the party there is a good chance that your fight or flight instincts will never be the same. Every time I say yes to a fun outing, make a commitment, etc., it is with the caveat that at any minute of any day, my daughter could have a seizure. If you want us to go on vacation, I will have likely looked up how close the nearest major hospital would be to us. There is no controlling it, no planning it. It could be mild or it could be life-threatening. There really is no “peace” to be found, it’s more of just a slow acceptance into your new normal. The part about the rescue meds? They only work if you see it or know that a seizure is happening; I can’t administer the life-saving meds if I’m asleep and don’t know it’s happening. While I try not to spend too much time thinking about it, SUDEP (Sudden Unexpected Death of someone with epilepsy) happens, and while there are monitors and even seizure-recognizing service animals, those have, so far, been denied to us by our insurance. For the first year after our daughter’s diagnosis, my husband and I didn’t have a single babysitter because the 13-year-old down the street is probably not ready to deal with a full-blown medical emergency. I say no to more things than others because, for us, finding a qualified individual capable of managing in a crisis is often nearly impossible.

With all that, she’s still just a typical four-year-old. With proper medication and dosage, she rarely has a seizure. She isn’t someone to be scared of; she doesn’t know there’s anything “different” about her because she has been Epileptic for the whole of her life that she remembers. She can run and jump and even bump her head. We know that being over-tired and over-heated are seizure-triggering for her, so we value sleep and shade. The acceptance of these changes in our lives was relatively easy. Her older brothers check the backpack for rescue meds and know their Sissy needs her hat and water bottle at the park. And, every day. EVERY. DAY. I thank God and science for intelligent people, modern medicines, doctors, nurses, and my little corner of the internet filled with other parents walking this road with us.