March is Brain Injury Awareness Month. I’ll be honest: outside of making my kids wear a helmet, I never really had a lot of “awareness” in regards to Brain Injury or Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI.) Most of what I knew was peripheral and not on my radar. Kids are resilient, they get bumps, bruises and even breaks, they bounce back; you can’t get wrapped up in worrying about the “what-ifs.” Up until the moment it happens to you, even when it was happening to me, I couldn’t really understand the magnitude of what a “bump on the head” could mean for my little boy, my family, and our whole future.

March is Brain Injury Awareness Month. I’ll be honest: outside of making my kids wear a helmet, I never really had a lot of “awareness” in regards to Brain Injury or Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI.) Most of what I knew was peripheral and not on my radar. Kids are resilient, they get bumps, bruises and even breaks, they bounce back; you can’t get wrapped up in worrying about the “what-ifs.” Up until the moment it happens to you, even when it was happening to me, I couldn’t really understand the magnitude of what a “bump on the head” could mean for my little boy, my family, and our whole future.

I’m not going to spend a lot of time talking about HOW my son ended up injured. Mostly because it was a series of the most unfortunate and innocuous moments, all leading up to a sort of one-in-a-million moment. There was capture the flag, there was a piggyback, there was a drop on a concrete sidewalk. Adults were supervising, no one had malicious intent and I don’t spend my time contemplating fault or blame. (Though my insurance company certainly did.)

My five-year-old sat up immediately after falling and hitting the back of his head. He barely cried. He never lost consciousness. His pupils were normal. He didn’t lose his balance. He was standing by the time I got to him. Shortly afterward, he threw up and told me he was a “little dizzy.” We happened to be with two pediatricians who looked him over (they even saw it happen) and informed me what I could gauge from a basic internet search: he didn’t meet the parameters for a scan at the ER, I could take him in, but there isn’t usually anything to DO other than to watch him, even if it was a concussion. When we arrived home I tried to do a movie and rest night, this went about as well as one may expect for an energetic five year old boy. I have vivid memories of him trying to RUN off the couch and tackle his older brother, not exactly ‘brain injury behavior.’ He ate a normal dinner, but he was slightly annoyed at how many times I asked him if he was okay, and he went to bed completely fine.

The next morning, I was still prepared to keep him home and watch him if he was displaying any symptoms of a concussion. He jumped out of bed, got dressed, and ate breakfast; we were 16 hours out, and he wanted to go to school, so I sent him. Even writing this, knowing what’s coming, I still can’t say I would have made a different call with the information I had. At 8:45, not even two hours later, I looked down at my phone and saw that it was the school calling, and I knew. ‘He’s pale, he’s throwing up, and I cannot keep him awake.’ I was out the door and in my van before we had even hung up. When I saw him, I had never seen him like that. He’s the class clown, he never stops talking or smiling, he’s every middle child stereotype you have ever heard; and he was laying on that bed looking like a shell of himself.

When we arrived at the ER after a not-so-legal drive, even the Pediatric ER doctor was reticent to scan him. She said she thought he had just freakishly gotten a stomach bug after a bump on the head. Only because he couldn’t really wake up and at my insistence that his behavior was so incredibly out of character did she send him to get an MRI. At this point, I was half-convinced that she was right, and I even told my husband to go ahead to the airport for his planned business trip. We had an MRI, and they said it was going to take about an hour to get the results. but in the meantime, they would get him some Zofran and turn down the lights. Ten minutes after we returned to the room, I heard a page for the doctor. We had seen that transport was on the line for her over the loudspeaker. Right as it clicked, I heard her on the phone and then watched her walk into our room. Then she walked straight to me, knelt down to look me right in the eye, and said, “He has fractured his skull, and I need to transfer him downtown RIGHT now.” Before I could really even respond, the EMTs were in the room with the stretcher. It’s one of those sort of white noise, change your whole world, cosmic shift moments.

Our ambulance had an ambulance escort. It all happened in less than ten minutes. Do you know what really made it hit home? We were right next to the helicopter and surrounded by ambulances, and my rescue vehicle-obsessed five-year-old didn’t even look. When we got downtown to the Children’s Hospital, and they opened the back doors, I saw an entire group of white coat-wearing doctors waiting for us in the ambulance bay, like a scene right out of Grey’s Anatomy. As they rushed us in, the Neuro attending looked at me and said, “In 27 years, I have never seen a kid do this.” My son fractured his Occipital bone. It is the thickest of the cranial bones, and the resultant trauma can be life-threatening. In addition to the sizeable fracture in his skull, he had a Traumatic Brain Injury or TBI. I was sitting there holding his hand, and, at one point, he opened his eyes. I told him I was there, and the doctor asked him, “Do you know who that is?” He was looking right at me and whispered, “No.”

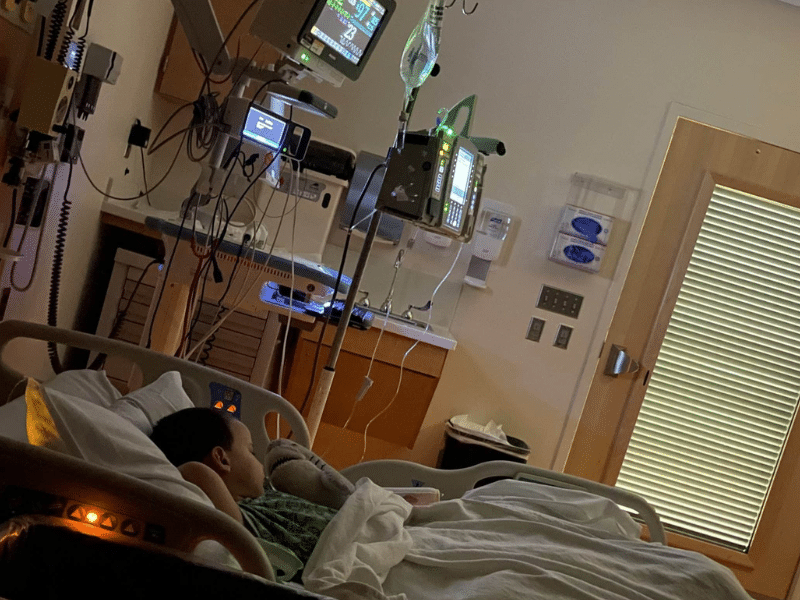

We spent a week in the PICU. Occupational therapists, physical therapists, speech therapists, and neuro exams were conducted every two hours. They had to remind him how to walk, he couldn’t figure out how to get the spoon to his mouth, he slept around the clock, in total darkness. This is the part where I tell you that he went from not recognizing his Mama to playing Go Fish in a week. Brain Injury doesn’t just magically heal, though. When we went home, he wasn’t allowed to walk without hands on him for two weeks. He had to take at least one nap a day. No overhead lighting. No screens for three months. No reading. No running. No jumping. No stairs on his own. The rule was “two feet on the ground- at all times.” We were outpatients at the TBI Clinic for an entire year. He missed six weeks of school, and when he went back, I had to go with him for one hour at a time, two hours and a half days. He couldn’t sit in a backless chair. I had to pick him up for fire drills because the sound was too loud. His teacher had to cover her overhead fluorescents. His neurologist told me that this kind of TBI, this kind of “bruise” to your brain, would be evident on his scans for the rest of his life. It’s been two years, and we still have to limit some of his physical activities because your brain is fragile. Your brain is everything about you. It’s your life. It’s his future. It’s every no-filter, hilarious comment he makes.

I’ll end with this: sometimes, while I’m scrolling, I see a kid on a bike without a helmet or a teen riding down the street on their skateboard, skiing, horseback riding, ice skating, you name it. I can’t control 98% of the things that can happen to my children. You aren’t raising “cool kids” if you don’t make them put on their helmets. You may be late because you have to find the right one and buckle it on. You may tell yourself that it’s just a couple of feet. There are countless stories similar to ours, and they will all tell you that protecting your brain and your head is one of the most important things that you can do. What happened to us wasn’t even one of those times where I would have thought to put a helmet on my child. So, in the instances when I CAN protect them, in every single opportunity, I will because your life can change in a single instance.