My mother was a four-year-old preschool teacher for many years. And not just any teacher, the kind of teacher every child should experience at least once in their lives. The kind of teacher who thinks like the kids. Whose eyes light up when describing an imaginary scenario to the class. Who revels in the accomplishments of her little charges. Who reworks lesson plans each year because there are always more fun ideas to try. Who never raises her voice because a glance across the room is enough to get a child’s attention. Who is, at heart, a child herself. She spent a lifetime teaching me, by her example, to love the messiness of childhood.

My mother was a four-year-old preschool teacher for many years. And not just any teacher, the kind of teacher every child should experience at least once in their lives. The kind of teacher who thinks like the kids. Whose eyes light up when describing an imaginary scenario to the class. Who revels in the accomplishments of her little charges. Who reworks lesson plans each year because there are always more fun ideas to try. Who never raises her voice because a glance across the room is enough to get a child’s attention. Who is, at heart, a child herself. She spent a lifetime teaching me, by her example, to love the messiness of childhood.

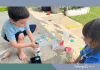

My mother knew that children learn through play. Through immersing themselves in different sensory experiences. Through making messes. Through getting lost in their imaginations.

Playdough, shaving cream with glue, finger paints, and crafts of all kinds were standard in our house. Cardboard rolls from paper towels, empty yogurt containers, and scraps of yarn and string were all saved carefully for future projects. Where others saw junk, she saw treasure to be turned into dollhouse furniture, rocket ships, and other creations. Where others saw too much work to clean up, she saw joy and the building blocks of development. To her, the messiness of childhood play wasn’t an inconvenience, it was a gift.

For a long time, I assumed all households ran this way. Then I became a pediatrician and started realizing that’s not the case. Many parents understandably shy away from mess and clutter. I tend to embrace it. My mother taught me that the magic of childhood is often found in messy play and objects that look like junk to adults but are treasures to young imaginations. This has been an adjustment for my much more mess-averse husband.

My mother lamented the changes she saw happening in childhood education and play over the decades. She never adjusted fully to the way our society began to erase much of the inherent messiness of childhood. Children spent more time on screens and with electronic toys, which left less and less time for self-directed play. As a result, she started to see classes of four-year-olds who in large part didn’t know how to create imaginary scenarios. She found herself spending the first weeks of school teaching her class how to play pretend!

Parents grew more afraid of messes and no longer gave playdough to their kids at home. What they didn’t realize is that play-dough may be a lot of fun, but it also strengthens crucial hand muscles needed to learn scissor-cutting and writing skills!

Kids stayed inside rather than exploring their surrounding world, not only did this stifle independence, but it also led to less balancing on logs, a skill that is actually good for many aspects of development: gross motor, vestibular development, and even pre-writing by following lines!

Kindergarten classrooms required more and more work and non-play-based exploration. Frequently changing standards took much of the creativity out of teachers’ hands.

I am grateful my mother raised me in an environment celebrating abundant imagination and wonder. It has greatly influenced the advice I give to parents as a pediatrician. It has also shaped how I encourage my own children to learn through messy play, wild imagination, and creative efforts.

Next time you find yourself cautioning your child to ‘not make a mess’, take a moment and consider whether the mess may in fact be worth it. Because mess and play are often how children learn the most about their world and themselves. Don’t get me wrong, I hate glitter as much as the next person. My heart sinks when I hear the sound of a cereal box dropping and spilling onto the kitchen floor. I groan a little when beads start to scatter off the table. Occasionally I intervene. But often I sit back and allow the mess. Sometimes I even encourage it!

Sometimes I jump right in, feet first, to the mud puddle with them. Those moments when I shed the trappings of adulthood and revel in the joy and messiness of childhood are magical. Embracing the joyful messiness of childhood and imaginative play is a legacy passed from my mother to me, and now from me to my children. These are the memories I hope my children carry into adulthood.